George Miller

A copywriter’s adventure in storytelling

I'm going to tell you a story. Are you sitting comfortably? Good. Then I'll begin.

This is a story about ...Story.

Or, more accurately, it is a story about how we’ve been exploring the application of storytelling principles to make copywriting at Bernadette more engaging from beginning to end.

Everyone loves a good yarn. Indeed, it's been proven that our brains are naturally hardwired to look for what we might call 'story beats' in everything from nursery rhymes to car commercials. Stories are based in the flow of time and as such, they have a beginning, a middle and an end — and it has been theorised that we often project this story structure onto the world around us to better make sense of our reality. Perhaps it was Mark Turner, renowned cognitive and linguist, who stated this best when he said: “Narrative imagining — story — is the fundamental instrument of thought. Rational capacities depend upon it. It is our chief means of looking into the future, or predicting, of planning, and of explaining.”

A quick trip to the shops. A holiday in Rio. A chance encounter with a stranger. It is intuitive for people to confer a sense of narrative on these events in their lives and colour them in with plot points and highlights in order to give meaning to subjective experience.

We’ve found that good copywriting can take advantage of this innate human tendency as a way to engage, entertain and deliver a compelling message. It is a powerful tool that allows us to curate belief, elicit emotional response and shape the thinking of our audiences.

As such, we think a foundational understanding of storytelling principle acts as a key component of any copywriter's toolkit. And, while it is true that style, grammar and well-composed syntax is often seen as the mainstay of any professional copywriter’s offering, it is rather our ability to construct narrative — to lead the reader on a journey — that allows us to deliver the messages we really want to land.

So where to begin?

Well, we already have. I’ve just treated you to a scene-setting introduction. A ‘beginning’ in which we’ve established the central themes of our ‘story’. Now, we’ll explore them in deeper complexity via a ‘middle’ and — if I manage to hold your attention for long enough — we’ll try and round things up with an impactful, thought-provoking ‘ending’.

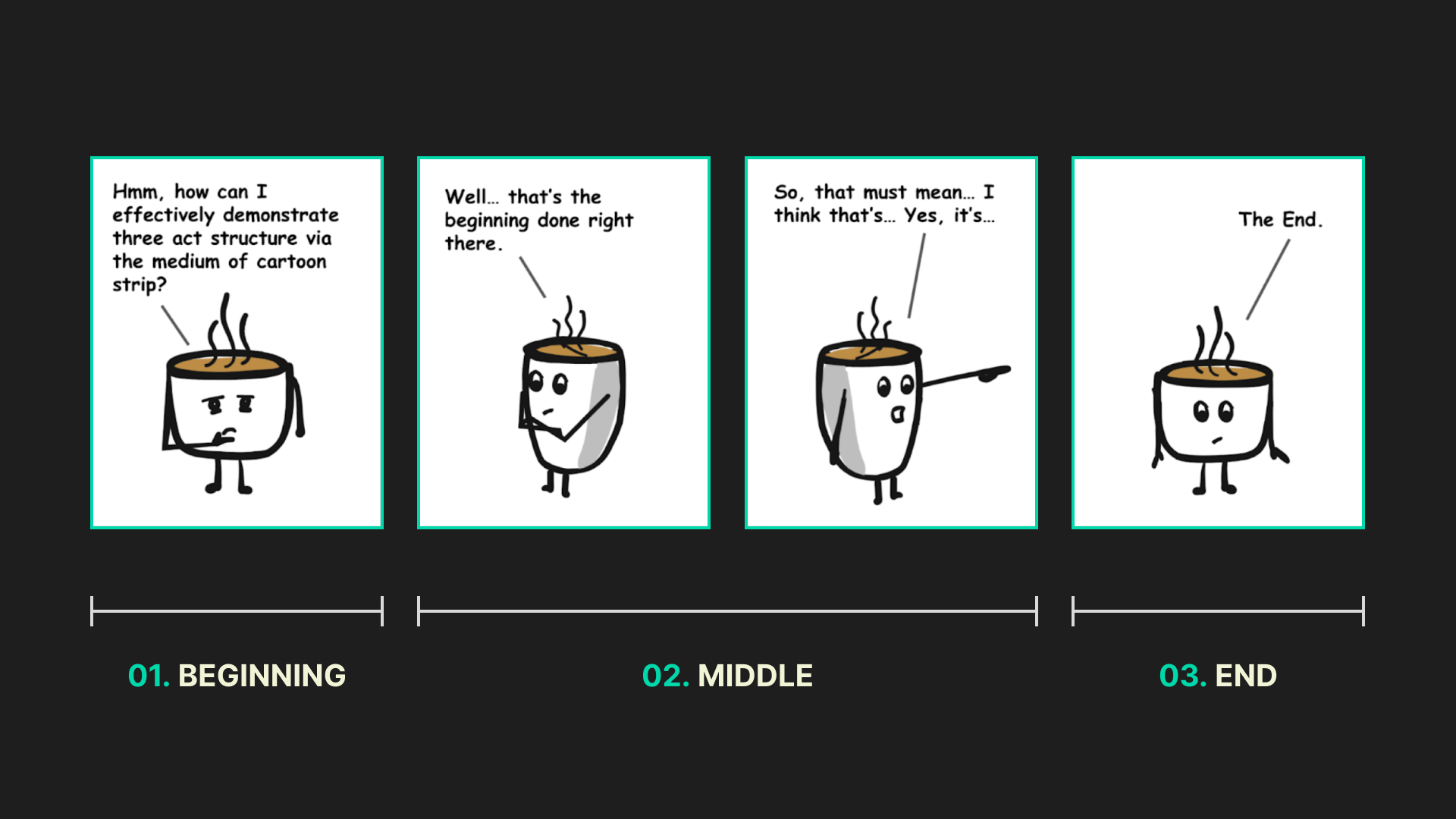

This framework is what’s commonly referred to as ‘three act structure’ and it permeates virtually every movie, play, novel, poem and video game (not Tetris) you’ve ever watched, read or played. It’s as old as time. Or, it’s at least as old as Aristotle’s work ‘Poetics’ (composed around 335 BCE) — which is one of the first theoretical texts to provide early critical insight into the basic foundations that make up storytelling, and proposed three act structure as the defining characteristic of any story.

But what might a practical application of this literary form look like when approaching something as concise and succinct as web copy? When working in support of Kia’s 2022 brand reinvention, embodied by a bold new mantra ‘Movement That Inspires’, we wanted to capture this sentiment in every single line of copy.

As anticipated, business specifications would invariably dictate page layouts that didn’t really lend themselves to comprehensive story structure. Nevertheless, we were able to take a storied approach on a more minute level — by applying simple three-part structure to paragraphs of body copy in a way that also captured the brand’s sense of forward motion.

So, rather than serving up car graphics with a dollop of ‘feature blurb’, we focused on framing each web module with a short definitive introduction, a more weighty middle section and a tidy ending. This simple use of the three act format helped inform direction and flow, and better supported a sense of natural rhythm — where we hit beats on the words we really wanted to emphasise.

As a result, we turned copy that might have otherwise read like this:

Electric vehicles are becoming more and more popular and, if you want to reduce your running costs and carbon footprint, maybe it’s time to think about whether it’s a good idea to invest in electric. The Kia EV range is designed to set a new standard, offering a family of eco-focused vehicles that’s redefining electric mobility.

That’s a ok, but the messaging is a little bit overloaded compared to this:

The future of electric mobility is right here. With the Kia EV6 range, we’ve reimagined how an electric car can look and feel — all while reducing your running costs and your carbon footprint. Our innovations have moved us towards the driving experience of tomorrow, today.

Ok, so it’s hardly The Great Gatsby, but there is the framework of story here that makes the copy neatly circular. The refined structure and pace also helps reinforce Kia’s brand Tone of Voice principles of being ‘purposeful’ and ‘fluid’. And that, as they say, is ‘a good start’.

The difficult ‘middle part’

Ok, but there’s more to telling a story than just framing it around a three act structure right?

Yes, that’s right. And, now that I’ve teased you down a proverbial rabbit hole of literary theory, it’s time for me to drag you head first into an intricate warren-like tunnel system of complex, abstract narrative thinking. This is a maze made up of the metaphysical — themes and motifs and character archetypes — many of which are mapped out in the so-called ‘Hero’s Journey’.

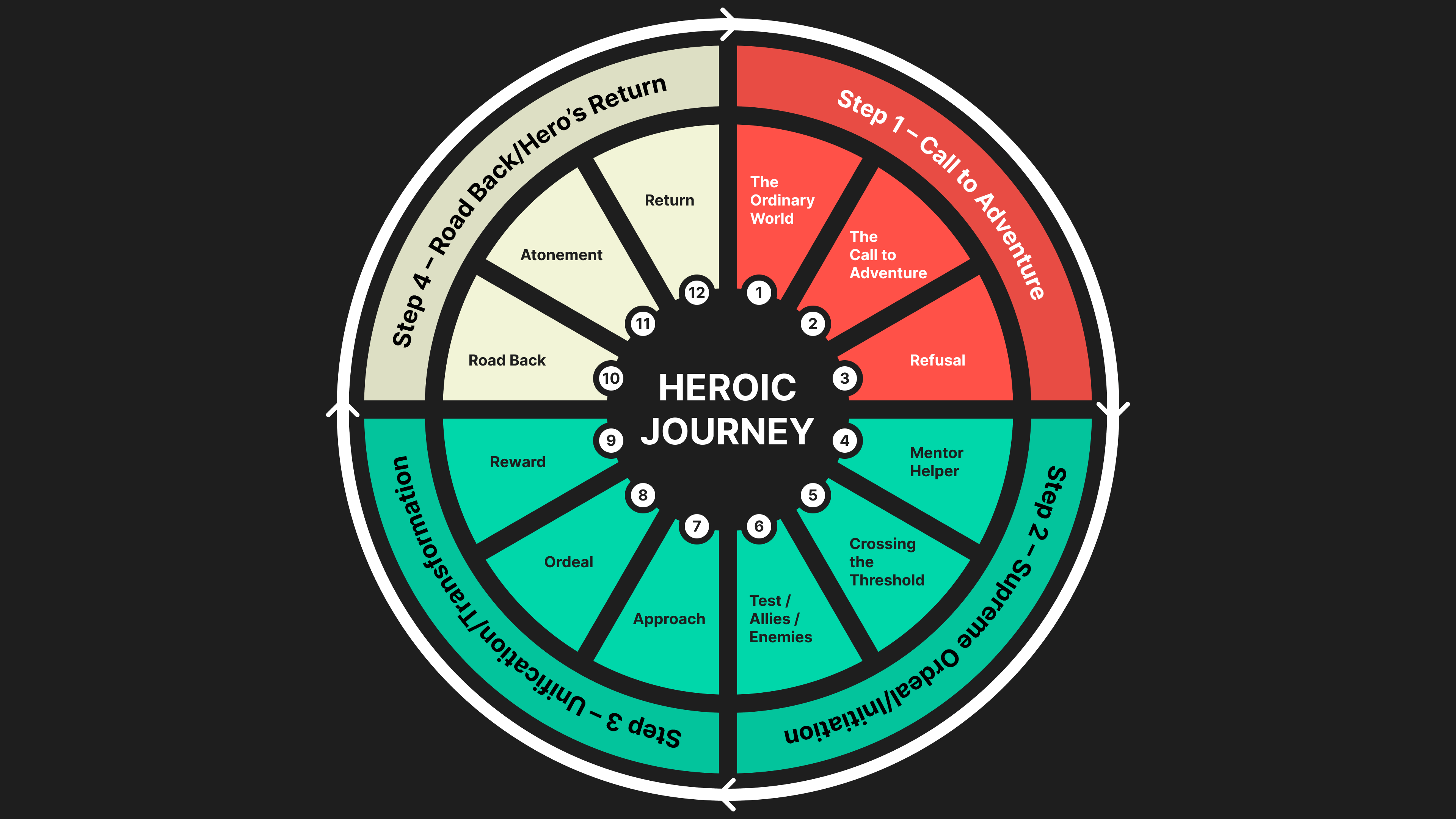

Also known as ‘the Monomyth’, The Hero's Journey was conceived by mythologist Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949). It was ideated as a universal narrative structure supposedly found in many myths, stories, and religious texts from around the world, and across multiple cultures. It is portrayed as a cyclical journey consisting of three main sections: ‘The Departure’, ‘The Initiation’ (often split into ‘inbound’ and ‘outbound’ subsections) and ‘The Return’.

See? There’s that three act structure again.

Without going too deeply into it, the model highlights a series of key events that usually happen to a story’s main protagonist as part of any given narrative.

To name but a few, the titular hero would, for example, receive an instigating 'Call to Adventure’, an inciting incident that would challenge them to undertake a journey. At some point later in the opening act they would likely 'Cross the First Threshold’, committing to the adventure by entering an unfamiliar realm of the unknown. This would then naturally lead them onto ‘a Road of Trials’, upon which the hero would face a series of tests or challenges. Finally, for the narrative to make sense, the protagonist would necessarily return back to their ‘ordinary’ world — bringing with them fresh insight with which to give the story a satisfactory conclusion.

The question we challenged ourselves with was this: Is any of this of any use when it comes to digital copywriting? It is afterall a writing discipline that generally calls for an approach to prose and language that’s simultaneously more technically streamlined and far less abstract.

This conflicts with The Hero’s Journey in the sense that it comes with a lot of heavy baggage and is saddled with more than its fair share of abstract interpretation. Many modern writers have come to take issue with Campbell’s observations on a number of levels. For some it has become an outmoded framework focused on a male-centric paradigm — with story components such as the ‘Atonement with the Father’ and ‘The Woman as Temptress’ straddling an uncomfortable space somewhere between the awkwardly esoteric and the casually misogynistic. In broader terms it has also been critiqued for being overly rigid and too prescribed to be considered universal, making it inapplicable to anything other than rambling sword-in-the-stone sagas with way too much time on their hands.

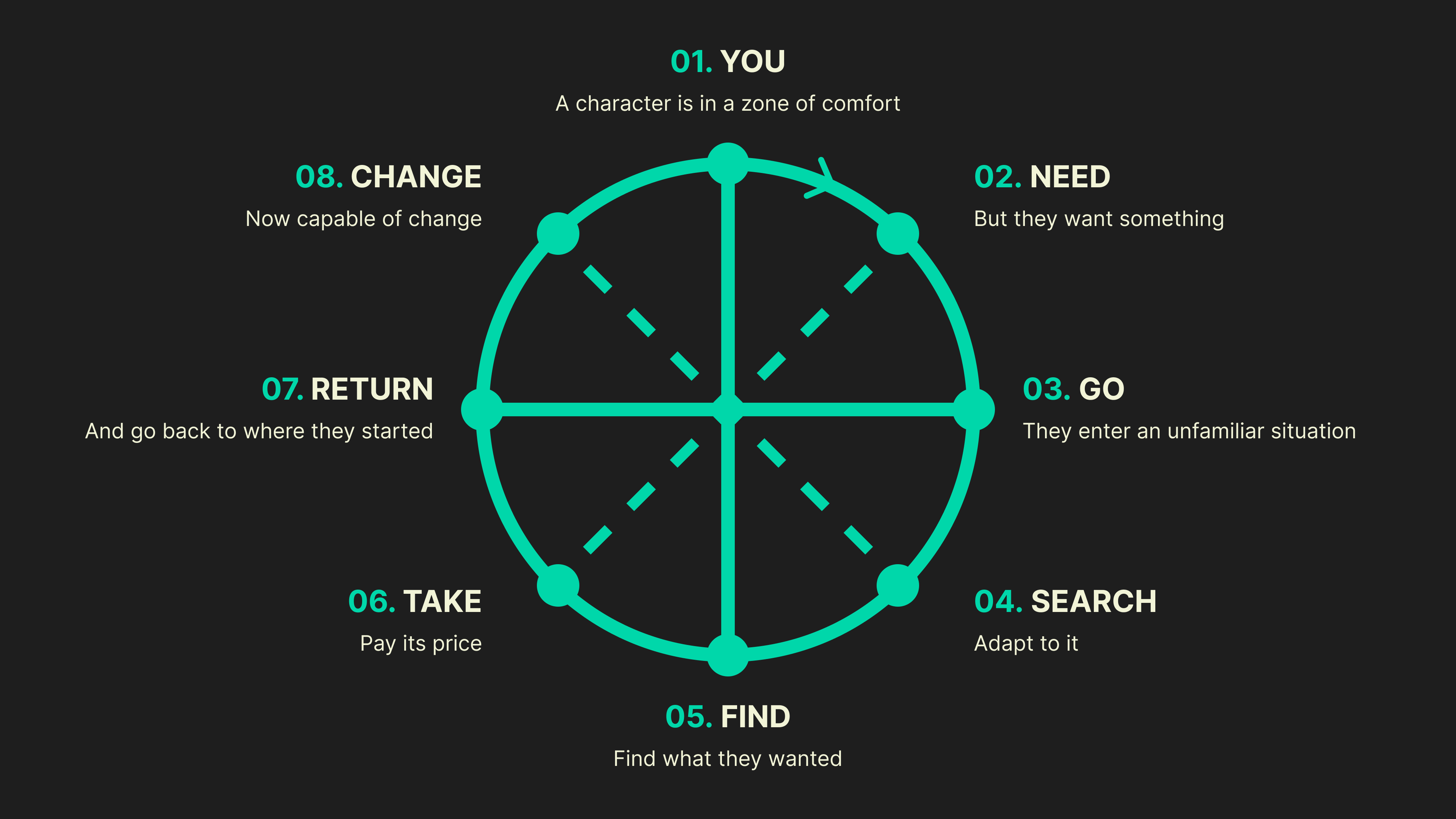

Thankfully, there’s similar narrative frameworks that provide the same essential structure, while reducing the density and ‘fluff’ of The Hero’s Journey. One such model that has gained increasing traction with writers in recent years is Harmon’s Story Wheel, a framework which observes the same core components of story as Campbell but strips things down to a bare minimum.

Conceived by Dan Harmon — creator of TV shows ‘Community’ and ‘Rick and Morty’ — it singles out 8 key story points consistent within storytelling, whether it’s your age old Greek tragedy or an episode of Star Trek.

Harmon’s model looks like this:

To summarise, the most essential elements in any story according to Harmon are as follows:

We’re introduced to our protagonist.

The protagonist demonstrates or articulates that they want something.

The protagonist is compelled to journey into unfamiliar territory.

The protagonist is required to adapt to this new environment.

The protagonist gets whatever it is they want, BUT

The protagonist pays a heavy price for it and loses something.

The protagonist returns to their point of origin.

The protagonist finds that they have changed.

As a working example, let’s look at Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) — George Lucas’ Monomyth-inspired space opera that consistently adheres to all of the above.

It starts with the introduction of a protagonist, Luke Skywalker, who wants to escape his homeworld, join a galactic rebellion and learn the ways of the Jedi. He’s compelled to answer a distress call from a princess which in turn presses him to journey into unfamiliar territory. This forces him to adapt as he attempts to rescue the princess. He gets what he wants by effectively joining the rebellion and becoming more attuned to ‘The Force.’ But, he pays a heavy price when his mentor Obi-Wan is slain and he’s forced to flee. With the destruction of the Death Star, balance is temporarily restored and Luke returns to a more familiar surrounding having been changed by a newly broadened sense of perspective.

These essential story beats can be found in most narratives, transcending the Monomyth template and defying genre. For example, would you believe me if I told you that The Dark Knight (2008), Pride and Prejudice (2005) and While You Were Sleeping (1996) were essentially the same movie?

It’s worth pointing out that removing one or more of these components doesn’t necessarily compromise good storytelling. For example, you can have a story where the protagonist doesn’t get what they want (Gone with the Wind, Citizen Kane, Casablanca) and you can have a story where the protagonist doesn’t change (The Big Lebowski, The Graduate, Forrest Gump). But, remove too many and a story will likely start losing all sense of cohesion to the detriment of its narrative (The Room, Battlefield Earth, Highlander II: The Quickening).

Next time you re-watch your favourite movie, try and keep an eye out to see how strictly it adheres to Harmon’s model (although, if you’re a massive David Lynch fan, I probably wouldn’t bother). There are always exceptions to the rules).

Another advantage of Harmon’s streamlined method over The Hero’s Journey is its adaptability and scalability — meaning not only can it be applied to a complete story, but it can be also applied to everything from acts, scenes, subplots, prologues, monologues, TV episodes, and more.

What makes Harmon's framework so useful is its support for structuring a story's ‘difficult middle section’, While it’s very easy to begin a story (just ask J.J. Abrams), it’s much harder to sustain an engaging narrative throughout.

This is where many story drafts run into difficulty. Very often writers are struck with a great concept for a story, they dive straight into it and they craft a strong opening with a good hook. They’ll also likely have some notion of an ending to write towards. But, as soon as they reach the story’s second act, the protagonist is suddenly set adrift with nowhere to go — passively reacting to events while they wait around for the story’s climax. But, for those stories that get made into movies and TV shows, by the time this happens there’s every chance that the audience’s investment will have waned (likely having been distracted by something more digestible on TikTok). This can all be avoided by implementing Harmon’s framework, by enabling writers to maintain a second act that holds its focus while avoiding the need for insubstantial, unrewarding narrative ‘filler’.

Taking a story approach to UX design

One could argue that these problems are content issues that beyond traditional narrative mediums also negatively affect digital mediums such as websites, UX flows, and CRM initiatives. Think about it, how often have you been on an enterprise website that opens confidently with a bold hero module presenting a clear focus on brand identity — and, at the bottom, you’re also able to find a definitive call-to-action that knows exactly what it wants you to do.

Only, the middle section seems to be just ambling along, content with a disparate array of repetitive, disjointed modules that make it feel like the whole page is just treading water, lost for something to say, waiting for the end.

So, going back to the question at hand — and taking into consideration the proven adaptability of Harmon’s model — we’ve begun applying his story wheel’s prescribed technique, beyond the bounds of conventional literature, to UX design and page structure.

To do this we’ve adapted Harmon’s guidelines to create a new content framework designed to co-opt some of this messaging and structure it more like an origin story.

Our repurposed framework looked like this:

Hero the brand identity

Emphasise the brand’s goal or mission

Recall an event in the brand’s history that put it on a journey

Outline how the brand has demonstrated innovation on the journey

Champion the brand’s success in completing its mission

Highlight a consequent challenge that came out of that success

Amplify the brand identity once again

Present the brand with a final concluding insight

By using this to reframe Berndette’s genesis story, we got this:

[Hero the brand identity]

We are Bernadette from VCCP. We specialise in creating new forward thinking products and services, supercharging existing customer experiences and activating brand campaigns.

[Emphasise the brand’s goal or mission]

Our mission? To seamlessly weave together brand, product, and customer experiences across the digital ecosystem. We want to apply our world-class digital strategy to craft products, experiences, and campaigns that resonate deeply with audiences.

[Recall an event in the brand’s history that put it on a journey]

The story began with a vision. Operating as VCCP CX our journey has been one of transformation and growth to become Bernadette — a fully-fledged team of 65+ creatives based in London and Prague.

[Outline how the brand has demonstrated innovation on the journey]

At Bernadette, innovation isn’t just a buzzword — it’s our creed. We've pioneered new categories, formats, and groundbreaking customer interactions. We’re not just imagining the future; we're crafting it, one digital solution at a time.

[Champion the brand’s success in completing its mission]

Our successes have been varied: From rejuvenating and supercharging pre-existing products and services to birthing entirely novel, industry-disrupting solutions. And at the heart of it all? Engaging digital brand experiences that spark connection and foster long-term advocacy.

[Highlight a consequent challenge that came out of that success]

With each success, the challenge rises. In a world that’s always online, always connected, and always evolving, the challenge is to remain at the forefront — to continually bridge the gap between strategy and execution, and to constantly redefine what's possible in the digital realm.

[Amplify the brand identity once again]

Bernadette is more than just a name; it's a mindset. We're a dedicated team that believes in creating a meaningful impact through our digital solutions everytime.

[Present the brand with a final concluding insight]

Our ethos is clear: We don't just create. We transform, innovate, and elevate digital experiences to a place that is above and beyond.

All’s well, that ends…

And that’s a wrap.

We think this Bernadette story arguably enjoys a pretty engaging copy treatment, benefitting from a comprehensive narrative structure that’s testament to the power of a good end-to-end journey.

What should we take from this? Does a storytelling approach to digital content work every time? The keen eyed reader might have noticed that this very article has implemented most of the narrative tools we’ve been talking about. So, I have to ask, did it work?

Well, you’ve made it to the end at least. And that’s something worth thinking about.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALEX SKEITH | SENIOR COPYWRITER

I’m a seasoned technical brand copywriter and content specialist with expertise in crafting and implementing Tone of Voice. I work with clients to help them refine that voice — and adapt it across multiple comms channels.